There aren’t many Buddhist or Shinto hashioki, which is a little odd because it seems like there’s a Buddhist temple or Shinto shrine on every other street corner in Japan. Maybe people think objects associated with religion or something sacred don’t belong at the dinner table, or maybe it’s just an untapped market.

The mokugyo is a kind of bell, carved from a single block of wood and struck with a wooden stick. They are traditionally made in the shape of a fish, although this example is in the shape of a dragon. This percussion instrument is used to set the rhythm during the chanting of sutras, particularly in Zen Buddhism.

The mokugyo is a kind of bell, carved from a single block of wood and struck with a wooden stick. They are traditionally made in the shape of a fish, although this example is in the shape of a dragon. This percussion instrument is used to set the rhythm during the chanting of sutras, particularly in Zen Buddhism.

These hashioki depict the base of a lotus plant, which is a water flower similar to a water  lily. The lotus is a sacred flower in Buddhism; Buddha traditionally sits on a lotus mount. The lotus is associated with marital love and harmony, but is also associated with death — which perhaps dampens the appeal of hashioki shaped like them.

lily. The lotus is a sacred flower in Buddhism; Buddha traditionally sits on a lotus mount. The lotus is associated with marital love and harmony, but is also associated with death — which perhaps dampens the appeal of hashioki shaped like them.

Perhaps the lotus has religious connotations because its’ roots thrive in the muddy muck of a marsh, and yet it produces handsome leaves and flower heads above water level. The lotus flower is shown in the blue and white hashioki here on the top. Portions of the large pond in Ueno Park in Tokyo are so filled with lotus plants by late summer that you cannot see the water, and it is an arresting sight, even when the blooms or pods are dried out. The lotus root or renkon is also a staple of Japanese cuisine; the two hashioki on the bottom here may remind you that you have seen this vegetable as a pickle or in stir fry’s.

If you’ve been to Japan you’ve undoubtedly seen rows of stone Jizo statues, many of them wearing red bibs around their necks, on the grounds of Buddhism temples. Rarely more than 18” high, the Jizo statues look like child monks, which is appropriate because they are associated with dead children, specifically children who were aborted. Jizo also protect pregnant women, and safeguard travelers, which explains why you also see them at crossroads, particularly in rural areas.

If you’ve been to Japan you’ve undoubtedly seen rows of stone Jizo statues, many of them wearing red bibs around their necks, on the grounds of Buddhism temples. Rarely more than 18” high, the Jizo statues look like child monks, which is appropriate because they are associated with dead children, specifically children who were aborted. Jizo also protect pregnant women, and safeguard travelers, which explains why you also see them at crossroads, particularly in rural areas.

The phoenix (hōō) is often a symbol of Buddhism is Japan, although it is also one of the symbols for the imperial family, specifically the empress. The most famous phoenixes in Japan are the pair that preside over the roof of the Hōō-dō hall at the famous Byōdō-in Buddhist temple in Uji, outside of Kyoto. The wooden Hōō-dō is the only original building still standing in the temple complex, and it dates from 1053. It sits on the edge of a large pond, and the pond’s reflection of the building’s center hall with corridors on either side is said to resemble a phoenix with outstretched wings. Uji is also a center for tea production, and the setting for the last chapters of The Tale of Genji.

The phoenix (hōō) is often a symbol of Buddhism is Japan, although it is also one of the symbols for the imperial family, specifically the empress. The most famous phoenixes in Japan are the pair that preside over the roof of the Hōō-dō hall at the famous Byōdō-in Buddhist temple in Uji, outside of Kyoto. The wooden Hōō-dō is the only original building still standing in the temple complex, and it dates from 1053. It sits on the edge of a large pond, and the pond’s reflection of the building’s center hall with corridors on either side is said to resemble a phoenix with outstretched wings. Uji is also a center for tea production, and the setting for the last chapters of The Tale of Genji.

The entrance to every Shinto shrine is marked by a torī gate which marks the boundary between the regular world and sacred space.. According to historian Basil Hall Chamberlain, the torī was originally a perch for sacred fowls which crowed to announce daybreak.(1) While this hashioki is made from sterling silver, and has the appropriate patina of a little tarnish, torī are usually painted bright red and often soar several stories high.

between the regular world and sacred space.. According to historian Basil Hall Chamberlain, the torī was originally a perch for sacred fowls which crowed to announce daybreak.(1) While this hashioki is made from sterling silver, and has the appropriate patina of a little tarnish, torī are usually painted bright red and often soar several stories high.

Shimenawa, or sacred rope of braided rice straw, also appear at the entrance to Shinto shrines, either wrapped around trees or large rocks, hanging over the entrance to a shrine building, or coiled around the base of a torī gate. Like those gates, shimenawa delineate the boundary of sacred space. Shimenawa are considered to have magical powers, although probably not in their hashioki form.

(1) Chamberlain, Basil Hall. Things Japanese: Being Notes on Various Subjects Connected with Japan. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 2007 (reprint of 1905 edition), p. 514.

The most elegant leaves in the world belong to a living fossil.

The most elegant leaves in the world belong to a living fossil.  poor soil and polluted air. Their resistant to pests, possibly because the outer covering of their seeds has a terrible smell. But perhaps the best proof of the gingko’s resilience is the fact that six small trees inside the blast zone in Hiroshima in 1945 survived the atom bomb, and continued to flourish there for many years.

poor soil and polluted air. Their resistant to pests, possibly because the outer covering of their seeds has a terrible smell. But perhaps the best proof of the gingko’s resilience is the fact that six small trees inside the blast zone in Hiroshima in 1945 survived the atom bomb, and continued to flourish there for many years.  The ginkgo owes the unusual spelling of its name to Engelbert Kaempfer, a German physician and naturalist who lived in Japan from 1690-1692. Kaempfer cataloged many Japanese plants and brought their seeds back to Europe; he apparently meant to record the name of this tree as “ginkyo” or “ginkio,” but made a clerical error.

The ginkgo owes the unusual spelling of its name to Engelbert Kaempfer, a German physician and naturalist who lived in Japan from 1690-1692. Kaempfer cataloged many Japanese plants and brought their seeds back to Europe; he apparently meant to record the name of this tree as “ginkyo” or “ginkio,” but made a clerical error. The term mingei, meaning “folk arts” or “folk crafts,” was created in 1926 by Japanese philosopher Yanagi Soetsu. According to Yanagi, the most beautiful objects a country could produce weren’t the works of individual skilled creative artists but were instead objects made by ordinary people for practical use which reflected patterns and values handed down by generations of their fellow countrymen.

The term mingei, meaning “folk arts” or “folk crafts,” was created in 1926 by Japanese philosopher Yanagi Soetsu. According to Yanagi, the most beautiful objects a country could produce weren’t the works of individual skilled creative artists but were instead objects made by ordinary people for practical use which reflected patterns and values handed down by generations of their fellow countrymen.

Mingei items often have a rough-hewn look, like this white hashioki with 3-D swirls on top, or these blue and green in the shape of a traditional Japanese kura storehouse and a bird. The pieces were formed by hand, not by machine, and they appear to have been glazed in a wood-ash

Mingei items often have a rough-hewn look, like this white hashioki with 3-D swirls on top, or these blue and green in the shape of a traditional Japanese kura storehouse and a bird. The pieces were formed by hand, not by machine, and they appear to have been glazed in a wood-ash  kiln. The kura storehouse piece is particularly appropriate because that is the shape of the MingeikanJapanese Folk Crafts Museum founded by Yanagi in a Tokyo suburb.

kiln. The kura storehouse piece is particularly appropriate because that is the shape of the MingeikanJapanese Folk Crafts Museum founded by Yanagi in a Tokyo suburb. surface to replicate the texture of a textile. The one on the right purposely combines different patterns, suggesting a mended article or a patchwork quilt. Both styles of decoration have mingei roots.

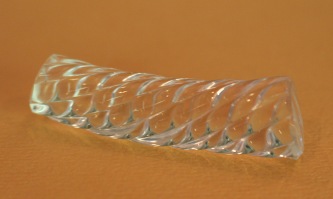

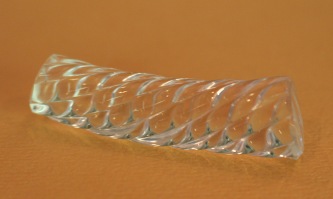

surface to replicate the texture of a textile. The one on the right purposely combines different patterns, suggesting a mended article or a patchwork quilt. Both styles of decoration have mingei roots. This last hashioki, which was labeled as a mingei piece by the vendor, is very handsome, but doesn’t really fit the definition of mingei. It’s too symmetrical, too orderly, and obviously made by a machine. I’ve included it here as a testament to the power of labeling.

This last hashioki, which was labeled as a mingei piece by the vendor, is very handsome, but doesn’t really fit the definition of mingei. It’s too symmetrical, too orderly, and obviously made by a machine. I’ve included it here as a testament to the power of labeling. In Japan lacquerware is also known as shikki or as nurimono, meaning “coated things.” This term alludes to way the items are produced, which involves applying multiple wafer-thin coats of lacquer to a base of wood or leather. It’s a time-consuming process because the lacquer has to dry between coats, and a little dangerous because the lacquer can cause severe allergic reactions before it dries and hardens.

In Japan lacquerware is also known as shikki or as nurimono, meaning “coated things.” This term alludes to way the items are produced, which involves applying multiple wafer-thin coats of lacquer to a base of wood or leather. It’s a time-consuming process because the lacquer has to dry between coats, and a little dangerous because the lacquer can cause severe allergic reactions before it dries and hardens. High end lacquerware, like this hashioki set from a famous nurimono shop in Tokyo, is sanded and polished between each coat of lacquer. The lacquer is sometimes tinted, which produces color that has depth, and sometimes enamel or golf leaf decorations are applied before the final coats of clear lacquer are applied. Lacquer can be so strong that it was used for body armor of samurai warriors.

High end lacquerware, like this hashioki set from a famous nurimono shop in Tokyo, is sanded and polished between each coat of lacquer. The lacquer is sometimes tinted, which produces color that has depth, and sometimes enamel or golf leaf decorations are applied before the final coats of clear lacquer are applied. Lacquer can be so strong that it was used for body armor of samurai warriors.

I think this last hashioki demonstrates the beauty of lacquerware. But the item is also interesting in itself; it is a rice scoop, a traditional tool used in threshing or the removal of the grains of rice from the stalks. The chopstick rest is very small, but according to the photos the items used during the rice harvest were often several feet long.

I think this last hashioki demonstrates the beauty of lacquerware. But the item is also interesting in itself; it is a rice scoop, a traditional tool used in threshing or the removal of the grains of rice from the stalks. The chopstick rest is very small, but according to the photos the items used during the rice harvest were often several feet long. The chrysanthemum is autumn’s most popular flower around the world, but the kiku is particularly celebrated in Japan. Starting in September, the month when they generally start to bloom in Japan, there are chrysanthemum shows and displays across the country, and long rows of chrysanthemums line the walkways of every temple and public building. The chrysanthemum is so popular that it’s a little surprising there aren’t more kiku hashioki.

The chrysanthemum is autumn’s most popular flower around the world, but the kiku is particularly celebrated in Japan. Starting in September, the month when they generally start to bloom in Japan, there are chrysanthemum shows and displays across the country, and long rows of chrysanthemums line the walkways of every temple and public building. The chrysanthemum is so popular that it’s a little surprising there aren’t more kiku hashioki. adorning temples and other buildings patronized by the Emperor. But when I counted the petals I saw that this hashioki has 12 petals, while the Imperial crest always has 16 rounded petals. Perhaps Imperial chrysanthemum hashioki are not marketed to mere mortals.

adorning temples and other buildings patronized by the Emperor. But when I counted the petals I saw that this hashioki has 12 petals, while the Imperial crest always has 16 rounded petals. Perhaps Imperial chrysanthemum hashioki are not marketed to mere mortals. This evergreen grass is omnipresent in Japan, both as a design motif, and as a material for many things, including chopstick res

This evergreen grass is omnipresent in Japan, both as a design motif, and as a material for many things, including chopstick res Bamboo shoots or sprouts are a popular vegetable in Japanese cuisine. They are served steamed, stir-fried or pickled, and prized for their sweet taste and firm texture. And cups and vases made from bamboo culms cut below the solid nodes that appear at regular intervals along the stems grace many Japanese tables. Bamboo cups are especially good for holding ice cold sake!

Bamboo shoots or sprouts are a popular vegetable in Japanese cuisine. They are served steamed, stir-fried or pickled, and prized for their sweet taste and firm texture. And cups and vases made from bamboo culms cut below the solid nodes that appear at regular intervals along the stems grace many Japanese tables. Bamboo cups are especially good for holding ice cold sake! Bamboo is also beautiful in an understated way. The long and narrow leaves make an attractive pattern, both in real life and as a decoration. Bamboo rarely flowers; some species only flower once every 60 to 120 years, and the plant often dies after it flowers. I like the way stalks sway and the leaves tremble when a gentle wind passes through a bamboo forest. There is a famous pathway through a bamboo forest in the town of Arashiyama, just outside of

Bamboo is also beautiful in an understated way. The long and narrow leaves make an attractive pattern, both in real life and as a decoration. Bamboo rarely flowers; some species only flower once every 60 to 120 years, and the plant often dies after it flowers. I like the way stalks sway and the leaves tremble when a gentle wind passes through a bamboo forest. There is a famous pathway through a bamboo forest in the town of Arashiyama, just outside of  Kyoto, that feels truly magical when you are surrounded by the rustling bamboo.

Kyoto, that feels truly magical when you are surrounded by the rustling bamboo.

But in fact this is a traditional Japanese pattern inspired by pavement.

But in fact this is a traditional Japanese pattern inspired by pavement.

My first trip to Japan was in the spring of 1991, when my husband had a 3-month visiting appointment to teach at the International University of Japan. IUJ is located just outside a small town called Urasa, 125 miles northwest of Tokyo, in a valley surrounded by rolling waves of mountains that often fade into the hazy distance. Seventy-three percent of Japan’s topography are mountains, and most of them are mountains like this: relatively low, strung together in long low mountains that are relatively low, and covered with green trees and shrubs for half of the year. During the colder months these mountains are often blanketed with 10 or 12 feet of snow, making the area a mecca for skiers. I think the striations on this pair almost look like ski runs.

My first trip to Japan was in the spring of 1991, when my husband had a 3-month visiting appointment to teach at the International University of Japan. IUJ is located just outside a small town called Urasa, 125 miles northwest of Tokyo, in a valley surrounded by rolling waves of mountains that often fade into the hazy distance. Seventy-three percent of Japan’s topography are mountains, and most of them are mountains like this: relatively low, strung together in long low mountains that are relatively low, and covered with green trees and shrubs for half of the year. During the colder months these mountains are often blanketed with 10 or 12 feet of snow, making the area a mecca for skiers. I think the striations on this pair almost look like ski runs. still very typical for Japan. Even though it’s a-mass produced piece, I like how the glaze is foggy and indistinct, and how the edges fade to white. It’s made by a company whose slogan is “pleasure of ordinary days,” and I certainly agree that one of those pleasures can be contemplating smoky mountains – even if you’re looking at them on the dining room table instead of seeing them in the distance.

still very typical for Japan. Even though it’s a-mass produced piece, I like how the glaze is foggy and indistinct, and how the edges fade to white. It’s made by a company whose slogan is “pleasure of ordinary days,” and I certainly agree that one of those pleasures can be contemplating smoky mountains – even if you’re looking at them on the dining room table instead of seeing them in the distance. When is a house more than a house? When it’s a hashioki, of course! Or in this case, when it’s actually FOUR hashioki.

When is a house more than a house? When it’s a hashioki, of course! Or in this case, when it’s actually FOUR hashioki.

Apparently there’s a connection between cats and good food, for this cat has the phrase Gochiso across her tummy, which is said at the end of a meal to indicate that it was delicious. Yoga enthusiasts may also recognize this cat is ironically in a down dog position.

Apparently there’s a connection between cats and good food, for this cat has the phrase Gochiso across her tummy, which is said at the end of a meal to indicate that it was delicious. Yoga enthusiasts may also recognize this cat is ironically in a down dog position. powerful message. This frog hashioki and white cat hashioki (in the middle) are inscribed with the single kanji fuku, meaning fortune or blessing. The maneki neko on the right stands on a base inscribed with the kanji for shuku, meaning celebrate or congratulate. These hashioki are therefore appropriate for almost any occasion or situation.

powerful message. This frog hashioki and white cat hashioki (in the middle) are inscribed with the single kanji fuku, meaning fortune or blessing. The maneki neko on the right stands on a base inscribed with the kanji for shuku, meaning celebrate or congratulate. These hashioki are therefore appropriate for almost any occasion or situation.

The mokugyo is a kind of bell, carved from a single block of wood and struck with a wooden stick. They are traditionally made in the shape of a fish, although this example is in the shape of a dragon. This percussion instrument is used to set the rhythm during the chanting of sutras, particularly in Zen Buddhism.

The mokugyo is a kind of bell, carved from a single block of wood and struck with a wooden stick. They are traditionally made in the shape of a fish, although this example is in the shape of a dragon. This percussion instrument is used to set the rhythm during the chanting of sutras, particularly in Zen Buddhism. lily. The lotus is a sacred flower in Buddhism; Buddha traditionally sits on a lotus mount. The lotus is associated with marital love and harmony, but is also associated with death — which perhaps dampens the appeal of hashioki shaped like them.

lily. The lotus is a sacred flower in Buddhism; Buddha traditionally sits on a lotus mount. The lotus is associated with marital love and harmony, but is also associated with death — which perhaps dampens the appeal of hashioki shaped like them.

If you’ve been to Japan you’ve undoubtedly seen rows of stone Jizo statues, many of them wearing red bibs around their necks, on the grounds of Buddhism temples. Rarely more than 18” high, the Jizo statues look like child monks, which is appropriate because they are associated with dead children, specifically children who were aborted. Jizo also protect pregnant women, and safeguard travelers, which explains why you also see them at crossroads, particularly in rural areas.

If you’ve been to Japan you’ve undoubtedly seen rows of stone Jizo statues, many of them wearing red bibs around their necks, on the grounds of Buddhism temples. Rarely more than 18” high, the Jizo statues look like child monks, which is appropriate because they are associated with dead children, specifically children who were aborted. Jizo also protect pregnant women, and safeguard travelers, which explains why you also see them at crossroads, particularly in rural areas. The phoenix (hōō) is often a symbol of Buddhism is Japan, although it is also one of the symbols for the imperial family, specifically the empress. The most famous phoenixes in Japan are the pair that preside over the roof of the Hōō-dō hall at the famous Byōdō-in Buddhist temple in Uji, outside of Kyoto. The wooden Hōō-dō is the only original building still standing in the temple complex, and it dates from 1053. It sits on the edge of a large pond, and the pond’s reflection of the building’s center hall with corridors on either side is said to resemble a phoenix with outstretched wings. Uji is also a center for tea production, and the setting for the last chapters of The Tale of Genji.

The phoenix (hōō) is often a symbol of Buddhism is Japan, although it is also one of the symbols for the imperial family, specifically the empress. The most famous phoenixes in Japan are the pair that preside over the roof of the Hōō-dō hall at the famous Byōdō-in Buddhist temple in Uji, outside of Kyoto. The wooden Hōō-dō is the only original building still standing in the temple complex, and it dates from 1053. It sits on the edge of a large pond, and the pond’s reflection of the building’s center hall with corridors on either side is said to resemble a phoenix with outstretched wings. Uji is also a center for tea production, and the setting for the last chapters of The Tale of Genji. between the regular world and sacred space.. According to historian Basil Hall Chamberlain, the torī was originally a perch for sacred fowls which crowed to announce daybreak.(1) While this hashioki is made from sterling silver, and has the appropriate patina of a little tarnish, torī are usually painted bright red and often soar several stories high.

between the regular world and sacred space.. According to historian Basil Hall Chamberlain, the torī was originally a perch for sacred fowls which crowed to announce daybreak.(1) While this hashioki is made from sterling silver, and has the appropriate patina of a little tarnish, torī are usually painted bright red and often soar several stories high.