I think of this pair as my Genji Monogatari hashioki, or as symbols of the famous Japanese novel The Tale of Genji.

I purchased them in the gift shop of Nagoya’s Tokugawa Museum, which is famous for owning three Genji monogatari emaki, or illustrated hand scrolls, which date from around 1130. They are three of the four survivors from of a set of 10 to 20 scrolls that once recounted stories from The Tale of Genji in painted pictures and calligraphy; the Gotoh Museum in Setagaya outside of Tokyo has a fourth scroll, while the others have been lost. These surviving scrolls are the oldest existent non-Buddhist scrolls in Japan, and are one of the National Treasures of Japan. The scrolls were not on display when we visited the museum, but we did see facsimilies of them.

The Tale of Genji is undoubtedly Japan’s most famous novel. It has also been described as the world’s oldest novel, and as the world’s first “modern novel” and first psychological novel. It centers on the story of Prince Genji, an uncommonly attractive and cultured “shining prince” whose grace, poetry skills and aesthetic sensibilities impressed all the aristocrats around him in the Heian period (794-1185) imperial court. Much of the novel centers on Genji’s affairs with a wide range of women; even though Genji was a serial romancer, most of his liasons treasured the time they spent with him as an exceptional experience. Later chapters of the novel recount tales of Genji’s descendants and others who wished to emulate him.

If we accept that these are indeed Genji Monogatari hashioki, then they depict Prince Genji and Murasaki, his greatest love, dressed in their finest court regalia. Some might say that this pair replicates the empress and emperor dolls that rule over the traditional display of dolls in some Japanese homes near Japan’s Girl’s Day national holiday on March 3 (please look for a future post on Hina matsuri). However, I think provenance is everything; this pair are my Tale of Genji hashioki. I’m sure the millions of readers who have been mesmerized by the novel during the past 1,000 years would agree.

To me the most amazing thing about The Tale of Genji is that it’s a very long novel, stretching over 1100 pages in a recent English translation by Royall Tyler. It was written by hand during stolen moments on odd lots of paper by a woman who worked as a lady in waiting to an empress in the early years of the 11th. century. The author didn’t have a typewriter or a computer or a dependable light source; she probably didn’t even have a copy of what she had already written as she wrote the middle or last chapters. Yet it is a coherent novel, with an orderly timeline, compelling stories, and developed characters.

There is no mention of hashioki in The Tale of Genji; hashioki made their appearance in Japan much later. There’s actually very little reference to food or the act of eating in the novel. In The World of the Shining Prince scholar Ivan Morris suggests that a Heian aristocrat’s diet consisted mainly of rice, rice cakes, fruit, vegetables, nuts and seaweed. Even the elegant and fastidious Prince Genji probably ate with his hands.

While it may seem strange to include hashioki depicting garuma, or ox carts, in a discussion about a romantic novel, these carts play a significant role in the book. Aristocratic women in Heian Japan were not meant to be seen by men outside their immediate family. So when they traveled to a temple or festival women rode in these ox-drawn vehicles, and were shielded from view by blinds or shutters. However, many assignations in the novel begin when a man catches an inadvertent glimpse of a woman in a cart, or after a man merely imagines how beautiful a woman riding in such a cart might be.

Lovers in The Tale of Genji wooed and responded through poetry; there are almost 800 five-line tanka poems interspersed throughout the story. They also exchanged flowers and blossoming branches, jars of incense, clothing and lengths of cloth. If only they had possessed hashioki! A stylish chopstick rest would have been the perfect thing to slip inside to a love letter or secretly pass to a paramour.

My Tale of Genji hashioki pair would never have made an appearance inside the novel. They are, alas, machine made and mass produced; they were purchased in a shop and not commissioned from an exclusive artisan. Prince Genji would have disdained them.

Instead Genji might have conspired to have a hashioki like this lacquered bow, fashioned from handmade washi paper that perhaps recreates the colors of the cape he wore to a tryst the night before, and then magically appearing on the breakfast tray of his new love.

Instead Genji might have conspired to have a hashioki like this lacquered bow, fashioned from handmade washi paper that perhaps recreates the colors of the cape he wore to a tryst the night before, and then magically appearing on the breakfast tray of his new love.

The object of his affections might have responded with an elegant hand-painted chopstick rest like this fan tied to poem proclaiming that even a fan couldn’t hide the  longing on her face that the shining prince will visit her once again tonight. At least, that’s the way it might have been, to paraphrase the last line of Royall Tyler’s translation of The Tale of Genji.

longing on her face that the shining prince will visit her once again tonight. At least, that’s the way it might have been, to paraphrase the last line of Royall Tyler’s translation of The Tale of Genji.

Maybe it’s because the blossoming of the plum tree signals is the first sign of spring. I’ve seen plum trees budding in Tokyo’s Ueno Park during the month of February, weeks before the cherry trees blossom.

Maybe it’s because the blossoming of the plum tree signals is the first sign of spring. I’ve seen plum trees budding in Tokyo’s Ueno Park during the month of February, weeks before the cherry trees blossom. spring.

spring.

In a small bowl sitting among other more expensive items were a mound of two different chopstick rests. The first one repeated the decorative motif of one of the two prizes in the MOA Museum’s collection, the “Tea-Leaf Jar with a Design of Wisteria” created by Nonomura Ninsei in the 17th century. The other one featured a portion from the museum’s other prize, the “Red and White Plum Blossoms” byobu or folding screen created by Ogata Korin in the 18th century. The hashioki were priced at just 250 JPY, or roughly $2.50 each at the exchange rate then.

In a small bowl sitting among other more expensive items were a mound of two different chopstick rests. The first one repeated the decorative motif of one of the two prizes in the MOA Museum’s collection, the “Tea-Leaf Jar with a Design of Wisteria” created by Nonomura Ninsei in the 17th century. The other one featured a portion from the museum’s other prize, the “Red and White Plum Blossoms” byobu or folding screen created by Ogata Korin in the 18th century. The hashioki were priced at just 250 JPY, or roughly $2.50 each at the exchange rate then. Museum is the first place I have seen chopstick rests that specifically replicate objects in a museum’s collection. I think it’s wonderful that this museum has made a small and inexpensive souvenir available to their visitors, allowing guests to go home and actually remember some of the artwork that they saw as they use their hashioki.

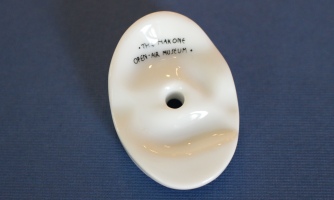

Museum is the first place I have seen chopstick rests that specifically replicate objects in a museum’s collection. I think it’s wonderful that this museum has made a small and inexpensive souvenir available to their visitors, allowing guests to go home and actually remember some of the artwork that they saw as they use their hashioki. museum in their gift shop. But this chopstick rest is not as satisfying as the MOA products. It’s an oddly shaped rest; there’s a grove for one chopstick tip on one side, and a less pronounced groove on the other side, and an unexplained hole in the middle. Maybe the idea is to burn a stick of incense between the tips of your chopsticks. In some ways this hashioki almost looks like a miniature sculpture, which is appropriate for a modern sculpture museum, but it doesn’t replicate any of the buildings or sculpture shown as the museum. Therefore, it does not seem as successful a souvenir as the MOA hashioki.

museum in their gift shop. But this chopstick rest is not as satisfying as the MOA products. It’s an oddly shaped rest; there’s a grove for one chopstick tip on one side, and a less pronounced groove on the other side, and an unexplained hole in the middle. Maybe the idea is to burn a stick of incense between the tips of your chopsticks. In some ways this hashioki almost looks like a miniature sculpture, which is appropriate for a modern sculpture museum, but it doesn’t replicate any of the buildings or sculpture shown as the museum. Therefore, it does not seem as successful a souvenir as the MOA hashioki.

Instead Genji might have conspired to have a hashioki like this lacquered bow, fashioned from handmade washi paper that perhaps recreates the colors of the cape he wore to a tryst the night before, and then magically appearing on the breakfast tray of his new love.

Instead Genji might have conspired to have a hashioki like this lacquered bow, fashioned from handmade washi paper that perhaps recreates the colors of the cape he wore to a tryst the night before, and then magically appearing on the breakfast tray of his new love. longing on her face that the shining prince will visit her once again tonight. At least, that’s the way it might have been, to paraphrase the last line of Royall Tyler’s translation of The Tale of Genji.

longing on her face that the shining prince will visit her once again tonight. At least, that’s the way it might have been, to paraphrase the last line of Royall Tyler’s translation of The Tale of Genji.

Over the years I’ve encountered this bird a number of times. It’s famous in the tiny (no pun intended) world of hashioki. So I was inspired to find out why this hashioki is so venerated.

Over the years I’ve encountered this bird a number of times. It’s famous in the tiny (no pun intended) world of hashioki. So I was inspired to find out why this hashioki is so venerated. Both Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples in Japan raise a little extra income by selling omikuji, or “sacred lot” paper fortunes. The omikuji are usually white paper strips that are rolled or folded. They are randomly dispensed to a fortune seeker after he or she drops 100 yen coin in a wooden box at a booth or into a vending machine.

Both Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples in Japan raise a little extra income by selling omikuji, or “sacred lot” paper fortunes. The omikuji are usually white paper strips that are rolled or folded. They are randomly dispensed to a fortune seeker after he or she drops 100 yen coin in a wooden box at a booth or into a vending machine. travel or childbirth, or something like that. Suggesting that the individual will find new and unusual hashioki doesn’t seem to be one of the standard fortune options, but there’s always hope. In any case, the fortune is derived by combining the two parts. So you could have a great blessing in business, or a small curse in travel, and so on.

travel or childbirth, or something like that. Suggesting that the individual will find new and unusual hashioki doesn’t seem to be one of the standard fortune options, but there’s always hope. In any case, the fortune is derived by combining the two parts. So you could have a great blessing in business, or a small curse in travel, and so on.

madai in Japanese, is one of Japan’s most popular fish. Like many other species of sea bream around the world, it is prized for its taste, whether it is sliced raw for sashimi, grilled over a charcoal fire, or poached and served whole. In Japan tai is considered a lucky fish because its name rhymes with medetai, meaning “auspicious.” It is often featured at the New Year, at weddings, and at other celebrations, and is considered to especially bestow good fortune when it brought to the table whole because of its appealing shape.

madai in Japanese, is one of Japan’s most popular fish. Like many other species of sea bream around the world, it is prized for its taste, whether it is sliced raw for sashimi, grilled over a charcoal fire, or poached and served whole. In Japan tai is considered a lucky fish because its name rhymes with medetai, meaning “auspicious.” It is often featured at the New Year, at weddings, and at other celebrations, and is considered to especially bestow good fortune when it brought to the table whole because of its appealing shape. Tai swim in the waters around all the Japanese islands. During the months of March and April tai move into coastal waters to spawn. At that time the skin of the fish turns red, and they are considered to have an especially good taste. During these months, which is also when cherry trees bloom in Japan, the fish are sometimes referred to as “cherry blossom tai.”

Tai swim in the waters around all the Japanese islands. During the months of March and April tai move into coastal waters to spawn. At that time the skin of the fish turns red, and they are considered to have an especially good taste. During these months, which is also when cherry trees bloom in Japan, the fish are sometimes referred to as “cherry blossom tai.”

That is why maneki neko are often pictured holding a large oval gold piece, like the cats here. The characters on the gold piece signify an archaic monetary measure equal to 18 grams of gold. Some maneki neko wear a bib with the character for takara, or treasure, like the blue and white stoneware example on the left below. The white hashioki on the right displays the kanji fuku, or good luck, which is a kind of fortune on its own.

That is why maneki neko are often pictured holding a large oval gold piece, like the cats here. The characters on the gold piece signify an archaic monetary measure equal to 18 grams of gold. Some maneki neko wear a bib with the character for takara, or treasure, like the blue and white stoneware example on the left below. The white hashioki on the right displays the kanji fuku, or good luck, which is a kind of fortune on its own.

fallen into disrepair. Once he passed through the gate the lord was suddenly inspired to repair and restore the temple. Temple administrators must put stock in this tale, because maneki neko charms are often sold at Japanese shrines and temple today. This smiling example, which has ball bearings inside that rattle when you shake it, seems like it might just be such a charm.

fallen into disrepair. Once he passed through the gate the lord was suddenly inspired to repair and restore the temple. Temple administrators must put stock in this tale, because maneki neko charms are often sold at Japanese shrines and temple today. This smiling example, which has ball bearings inside that rattle when you shake it, seems like it might just be such a charm. Some maneki neko beckon with their right paw, and some beckon with their left paw. There is some debate about the significance of which paw is raised. Some say that a raised right paw indicates general good luck, while a raised left paw specifically asks for customers or financial luck. But it probably boils down to the whimsy of the artist who made the pieces.

Some maneki neko beckon with their right paw, and some beckon with their left paw. There is some debate about the significance of which paw is raised. Some say that a raised right paw indicates general good luck, while a raised left paw specifically asks for customers or financial luck. But it probably boils down to the whimsy of the artist who made the pieces.

Like the tanuki, the kappa is one of Japan’s bad boys. However this mischievous water imp is entirely imaginary. The kappa is reportedly the size of a child, a body covered with scales, webbed hands and feet, and shaggy bobbed hair. They live in rivers, which explains their piscine characteristics and reportedly fishy smell. Kappa supposedly have double-jointed arms and legs, which undoubtedly helps them perform their most heinous crime: dragging innocent humans, especially children, into the water and drowning them. But we could argue that kappa are not entirely bad, because they are a convenient scapegoat for parents to use to warn their children about playing too close to the water.

Like the tanuki, the kappa is one of Japan’s bad boys. However this mischievous water imp is entirely imaginary. The kappa is reportedly the size of a child, a body covered with scales, webbed hands and feet, and shaggy bobbed hair. They live in rivers, which explains their piscine characteristics and reportedly fishy smell. Kappa supposedly have double-jointed arms and legs, which undoubtedly helps them perform their most heinous crime: dragging innocent humans, especially children, into the water and drowning them. But we could argue that kappa are not entirely bad, because they are a convenient scapegoat for parents to use to warn their children about playing too close to the water. which holds a liquid which is the source of their powers. Somewhere in their mythic history a folktale story teller decided to have some fun with the kappa, claiming that kappa are obsessively polite, and that when they bow the liquid spills out and they become powerless.

which holds a liquid which is the source of their powers. Somewhere in their mythic history a folktale story teller decided to have some fun with the kappa, claiming that kappa are obsessively polite, and that when they bow the liquid spills out and they become powerless.